Introduction: The Tax on Investment Success

![]()

For every investor who successfully buys low and sells high, realizing a profit is the ultimate goal, signaling a fruitful return on careful financial planning and calculated risk. This profit, however, triggers an often-complex and significant obligation to the government known as Capital Gains Tax.

Understanding the mechanics of this specific tax—which applies to the profit made from selling an asset like stocks, real estate, mutual funds, or even cryptocurrency—is arguably as crucial as understanding the investment itself. Failing to properly account for capital gains can lead to unexpected tax liabilities, costly penalties, and a substantial reduction in the investor’s actual retained wealth.

Unlike ordinary income tax, which is applied to wages and salaries, capital gains tax is levied specifically on the gainfrom the sale of a capital asset. This gain is calculated as the difference between the asset’s purchase price (the cost basis) and its final sale price.

The complexity intensifies because the tax rate applied is not static; it is heavily dependent on how long the asset was held before it was sold, creating a critical distinction between short-term and long-term gains. Navigating this timing factor is the key to strategic tax minimization.

A proactive approach to managing capital gains requires moving beyond simply calculating the profit after the sale. It demands meticulous record-keeping, a deliberate strategy around holding periods, and a keen awareness of available tax-advantaged accounts and loss-harvesting techniques. This comprehensive guide will meticulously dissect the definition and calculation of capital gains, explain the dramatic difference in tax rates between short-term and long-term holdings, and provide actionable, low-risk strategies for legally minimizing your annual tax bill. Mastering these concepts ensures that your investment success translates into maximum retained wealth.

Part I: Defining and Calculating Capital Gains

![]()

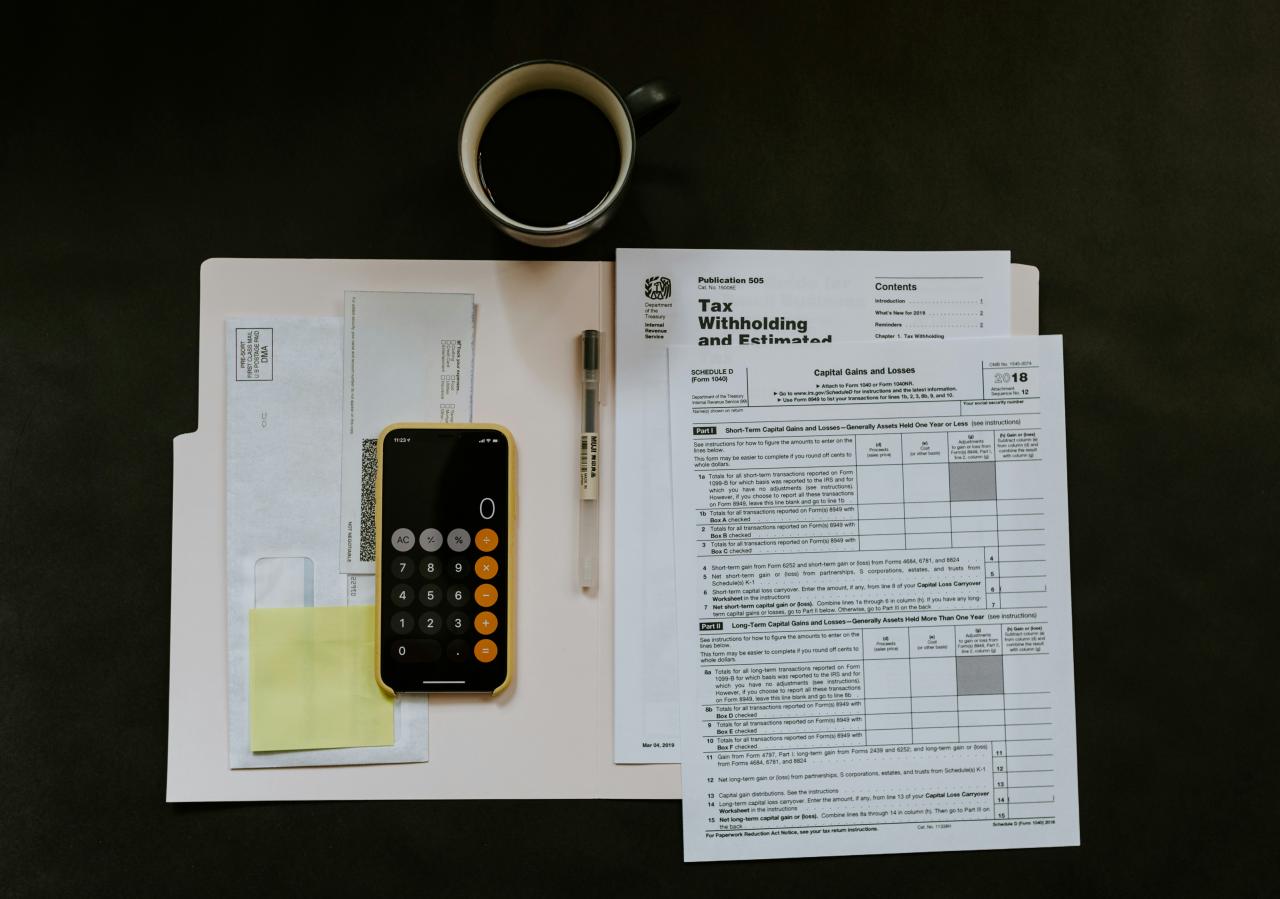

Before you can strategize about minimizing the tax, you must first accurately understand what a capital gain is and how it is mathematically determined.

A. What is a Capital Asset?

A capital asset is virtually any property you own for personal use or investment purposes.

- Common Examples: This includes stocks, bonds, mutual funds, real estate (except your primary residence for the exclusion rules), artwork, jewelry, and cryptocurrency.

- Exclusions: Items that are explicitly not capital assets include inventory held for sale (for a business), or depreciable property used in a trade or business.

B. Calculating the Gain (The Cost Basis)

The profit (gain) subject to tax is calculated by subtracting the cost basis from the sale proceeds.

- Sale Proceeds: This is the total amount of money received from the sale of the asset.

- Cost Basis: This is the original purchase price of the asset plus any commissions paid and any costs associated with its purchase or significant improvement (e.g., closing costs and renovation expenses for real estate).

- The Gain: The capital gain is the profit: $\text{Sale Proceeds} – \text{Cost Basis} = \text{Capital Gain}$. It is this final figure that is subject to the capital gains tax rate.

C. The Critical Role of Holding Period

The length of time you hold the asset determines the tax rate applied to the profit. This is the most crucial distinction in capital gains taxation.

- Short-Term Capital Gain: Applies to assets held for one year or less.

- Long-Term Capital Gain: Applies to assets held for more than one year (366 days or more).

Part II: Short-Term vs. Long-Term Tax Rates

![]()

The difference in tax treatment between short-term and long-term gains forms the foundation of all capital gains tax strategy.

A. Short-Term Capital Gains (Ordinary Income)

Short-term gains are taxed at the highest rates because they are treated the same as regular wage income.

- Tax Rate: Short-term capital gains are added to your ordinary income (salary, wages, interest income) and are taxed at your marginal income tax bracket.

- Highest Cost: This means that short-term gains can be taxed at rates as high as $37\%$ (the top ordinary income bracket), making frequent, short-duration trading a highly tax-inefficient investment strategy.

- Incentive for Patience: The high tax rate on short-term gains is a deliberate disincentive designed by the government to encourage long-term investment rather than speculative trading.

B. Long-Term Capital Gains (Preferential Rates)

Long-term gains benefit from significantly lower, preferential tax rates that are often the goal of serious investors.

- Tax Rate: Long-term capital gains are taxed at three possible tiers: $0\%$, $15\%$, or $20\%$. These rates are based on the taxpayer’s total taxable income (including wages and short-term gains).

- $0\%$ Tax Bracket: Many low-to-moderate-income taxpayers (those whose total income falls below a certain threshold) pay $0\%$ federal tax on their long-term capital gains, making asset sales completely tax-free.

- $15\%$ and $20\%$ Brackets: The $15\%$ rate applies to most middle- and high-income earners, and the $20\%$ rate is reserved for the highest income brackets. Even the highest $20\%$ long-term rate is substantially lower than the maximum ordinary income rate of $37\%$.

C. State Taxes

It is vital to remember that all capital gains—both short-term and long-term—are also subject to state and local income taxes, which vary widely depending on the state of residence.

Part III: Tax-Advantaged Accounts (The Best Defense)

The single most effective way to eliminate or defer capital gains tax is by utilizing specific accounts designed by the government for retirement and education savings.

A. Retirement Accounts (Tax Shield)

Accounts like 401(k)s and IRAs protect investments from capital gains tax entirely, while they are growing.

- Tax-Deferred (Traditional): In a Traditional 401(k) or IRA, all capital gains, dividends, and interest generated are shielded from tax while they remain in the account. Taxes are only paid upon withdrawal in retirement, and then they are taxed as ordinary income.

- Tax-Free (Roth): In a Roth IRA or Roth 401(k), the growth is completely tax-free. No capital gains tax is paid, and qualified withdrawals in retirement are also tax-free, making it the most powerful vehicle for long-term compounding.

- Strategic Placement: Investors should prioritize placing high-growth, high-turnover investments (which would generate frequent, taxable gains) inside these tax-advantaged accounts first.

B. College Savings Accounts (529 Plans)

529 plans are designed for education savings but offer a similar tax-free growth benefit.

- Tax-Free Growth: Investments inside a 529 plan grow tax-free.

- Tax-Free Withdrawal: Withdrawals are completely tax-free at the federal level (and often state level) provided the funds are used for qualified educational expenses (tuition, room, board, and often K-12 tuition).

Part IV: Tax Minimization Strategies (Harvesting and Timing)

For investments held in taxable brokerage accounts, investors can actively employ strategies to legally offset realized gains.

A. Tax-Loss Harvesting (Offsetting Gains)

Tax-Loss Harvesting is the strategy of deliberately selling assets that have lost value to offset the tax liability generated by assets that have gained value.

- The Offset Principle: Capital losses (selling an asset for less than its cost basis) can be used to offset realized capital gains. Selling $5,000 worth of profitable stock and simultaneously selling $5,000 worth of losing stock results in a net capital gain of zero, eliminating the tax liability.

- Deductible Losses: If total capital losses exceed total capital gains for the year, the investor can deduct up to $3,000 of that net loss (or $1,500 if married filing separately) against their ordinary income. Any remaining loss is carried forward to future tax years.

- The Wash Sale Rule: Investors must be extremely careful to avoid the Wash Sale Rule. This rule states that you cannot claim a tax loss if you buy the substantially identical stock or security within 30 days before or after the date of the sale.

B. Controlling the Holding Period

The most straightforward way to reduce your tax bill is to manage the duration of your investment.

- The One-Year Mark: If you have an asset with a significant unrealized gain, hold it for at least 366 days to convert the profit from the high ordinary income rate (up to 37%) to the favorable long-term capital gains rate (max 20%).

- Timing the Sale: For high-income earners who anticipate a drop in income next year, or for those nearing retirement, delaying the sale until the income level drops may allow them to access the lower $15\%$ or even $0\%$ long-term bracket.

C. Donor-Advised Funds (Charitable Giving)

For philanthropic investors, donating appreciated assets can be a highly tax-efficient strategy.

- Donating Stock: Instead of selling appreciated stock (incurring a capital gain) and then donating the cash, donate the stock directly to a qualified charity or a Donor-Advised Fund (DAF).

- Double Benefit: The investor receives two benefits: 1) They get an immediate tax deduction for the fair market value of the stock, and 2) They completely avoid paying capital gains tax on the appreciation.

Conclusion: Strategic Investment and Tax Timing

Successfully minimizing your capital gains tax bill is a process of strategic investment timing and meticulous use of government-sanctioned tax shields. The cornerstone of this strategy is understanding and leveraging the vast difference in tax rates between short-term gains (taxed as ordinary income up to 37%) and long-term gains (taxed at the preferential rates of 0%, 15%, or 20%).

The most powerful defense against capital gains tax is the consistent utilization of tax-advantaged accounts like the Roth IRA, where all appreciation and withdrawals are shielded from future taxation. For assets held in taxable accounts, investors must diligently manage the holding period, ensuring assets are held for more than 365 days to qualify for the favorable long-term rates.

Furthermore, proactive use of tax-loss harvesting provides a crucial method for legally offsetting realized gains with realized losses. By mastering the core concepts of cost basis, holding periods, and tax-loss utilization, investors secure maximum financial retention and ensure their investment success is not unduly penalized.